The wheat, the weeds and the wait

/Jesus used another illustration. He said, “The kingdom of heaven is like a man who planted good seed in his field. But while people were asleep, his enemy planted weeds in the wheat field and went away. When the wheat came up and formed kernels, weeds appeared.

The owner’s workers came to him and asked, ‘Sir, didn’t you plant good seed in your field? Where did the weeds come from?’

He told them, ‘An enemy did this.’

His workers asked him, ‘Do you want us to pull out the weeds?’

He replied, ‘No. If you pull out the weeds, you may pull out the wheat with them. Let both grow together until the harvest. When the grain is cut, I will tell the workers to gather the weeds first and tie them in bundles to be burned. But I’ll have them bring the wheat into my barn.’

— Matt. 13:24-30, God’s Word Translation

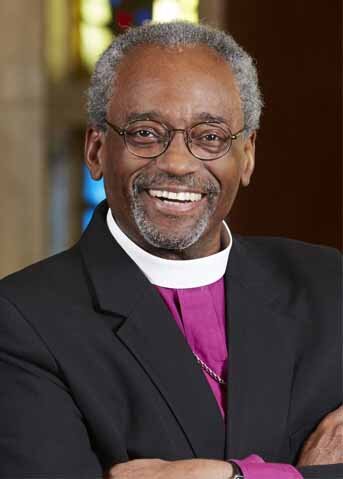

In a recent sermon on the parable of the wheat and the tares, the Rev. Anne Moore compared the workers’ reaction to their employer’s answer (‘the enemy did this’)—their desire to do something immediately to get rid of those weeds—to our own observations and imperatives when we see evil in the world.

The cancer returns; the job is eliminated; the relationship ends; depression sets in; a loved one’s life is cut short; a congregation is divided; war forces thousands to flee as refugees; the world turns its back on people in need. 'Why doesn't God DO something?’ we agonize.

Simply by expressing that we prove we know there are evil forces in the world we cannot eliminate or control, she noted. We have the sense this is not what God intended, and that sense can be near unbearable. So we may be tempted to explain the evil by assigning it to some greater design of God.

'Don’t worry, it’s still part of God’s plan;' or 'He never gives us more than we can handle;' or 'His purpose for this will reveal itself in time.' Yet all these explanations, meant to be comforting or helpful, end up blaming God for tragedy.

“God does not will evil for us in any way, shape or form," Anne assured listeners. "Our tragedies are not part of God’s plan. God never, ever, wants us to suffer. When we do, when tragedies strike, it is the result of evil, not God. God created us, loves us, and as Paul wrote, God works for the good in all things.”

Remember, ‘an enemy has done this!’ as the farmer in the parable reported to the workers wondering about the weeds.

But the question remains: Why doesn’t God do something? This parable, and others, don’t provide a direct answer, Anne admitted. What they do show is that God’s sovereign rule over the world proves not quite as straightforward as we sometimes imagine or wish.

She offered some excellent questions posed by Bishop N. T. Wright as helps in thinking this through.

Would people really like it if God were to rule the world directly and immediately? Every thought and action would be weighed, instantly judged, and, if necessary, punished using the scales of His absolute holiness. If the price of God stepping in and stopping a campaign of genocide was that He would also have to rebuke and restrain every other evil impulse, including those we all still know and cherish within ourselves, would we be prepared to pay that price? If we ask God to act on special occasions, do we really suppose that He could do that simply when we want Him to, and then back off again the rest of the time?

Instead of answering the why’s, the parable really presents the need to wait. Yes waiting is difficult, but like the farmer, we must wait for harvest time.

The obvious truth is we cannot control God. We wait, and we pray, for the harvest.

As Jesus more fully explains the parable to his disciples, the point of waiting becomes even clearer. He himself, Jesus says, is the ‘farmer’—the one sowing the good seed. The field is ‘the world’; the good seed are children of the Kingdom. The ‘tares’ (weeds) belong to the devil’s domain, and the enemy sowing them is Satan (Matt 13: 36-43).

So the point of ‘delayed judgement’? Many more will be saved!

-----------------------------------------

Note: An alternate translation for tares or weeds—‘darnel’—is likely the best, adding remarkable depth to Jesus’ parable. Wheat and darnel usually grow in the same production zones and look almost exactly the same until the kernel-containing heads of the plants form. Even then, the differences are slight. Some call darnel ‘false wheat’, others wheat’s ‘evil twin’. Its official name, L. temulentum, comes from a Latin word for 'drunk' since when people eat its seeds, they get dizzy, off-balance and nauseous. High doses cause death.